For reviews of Junction Reads’ titles, check out the Homepage.

Mackenzie Nolan’s novel, VEAL, opens with a dedication as important as any of the stunning sentences you’ll find within the pages of this extraordinary debut: “For all the women who are made to answer for the violence of men. I will always be in your corner. Give them hell.”

VEAL opens with Lawrence (Delores) leaving a life behind – a life ruined because in trying to make her mother happy, she nearly destroyed herself – and starting a Library Sciences program at Mistaken Point University. She brings along Stasia, her best friend, her first love, and now her roommate in a town made famous for the gruesome murders and dismembering of several young women. When she takes a job as bookkeeper at a funhouse/arcade, she is immediately drawn to the owner, Francesca Delores, a woman whose last name reflects Lawrence’s first name, a mirror image of one another. Lawrence’s coworker Pippa knows more about the murders and how Franky lost her arm, and the monster still hunting women in Mistaken Point.

The four women investigate and hunt down the monster of Mistaken Point, police drop the ball, don’t interview key witnesses, ignore or fumble the evidence, only make “an arrest because it was served to them on a silver platter” and the police certainly don’t believe the women. “Women are only believed when they’re dead.” And the reader is trapped in a frustratingly familiar world.

An intimate portrayal of what it is to be a woman in the today, an exploration of all we carry down from our parents, and a moving friendship story, and love story – what does it mean to be loved in a world where your body is an object, when your body is prey? Reading VEAL, I felt as though I’d been invited to a staff room filled with women who’ve worked together for decades. The intimacy of dialogue, the familiarity of the narrative voice, and the honesty gifted from one woman to another, Mackenzie Nolan gave me a safe space to imagine what I’d do, if only I had an axe and three fearless friends.

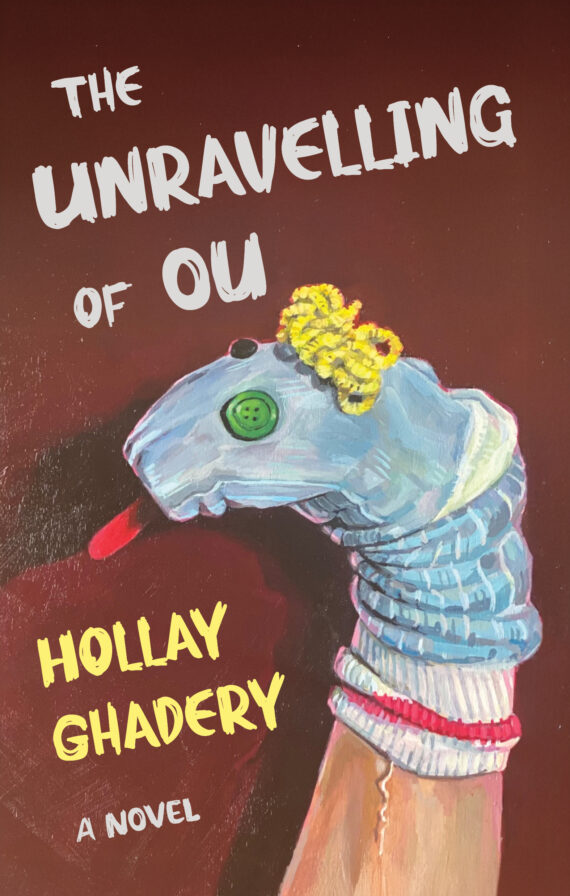

As Minoo thinks of her first child, “the last time she kissed him before leaving him” forever, “pressing her lips to the tender chasm above his belly button…” she decides to bring her sock puppet Ecology Paul to the hospital to meet her new grandchild – as a buffer between herself and the swell of emotions. When her daughter tells her she must get rid of the puppet or never see her grandchild, Minoo’s life unravels as she drives home from the hospital.

A novel that expresses the unexpressable pain of motherhood, of being a woman inside a body that is “a soft, needy animal” of the desperate escape from shame that defines Minoo’s existence. She discovers masturbation and is told it’s disgusting; she’s told “menstruation may be natural, but that didn’t stop it from being vulgar”; she’s told that “one girl was more trouble than ten boys” and she comes to believe that “her body was and had always been a wound she had to endure.” She doesn’t know the meaning of ovulation or what is a cervix. The only way to escape her body is to crawl inside another’s, someone who just happens to be a woollen camp sock puppet with pipe cleaner hair and unrollable eyes.

There were so many moments reading THE UNRAVELLING OF OU that I swallowed hard against the swell of my own emotions, as a mother, as a daughter, as a woman coming to terms with my own painful experiences living inside a body that often doesn’t feel like it belongs to me. It might be difficult to express the urgency I feel – every reader needs to experience the perfect emotionality of Hollay Ghadery’s prose because she gets to the heart of living, not only in the body of a woman, but inside the mind of someone who dreams of being “untethered to the world”.

Grief is expressed as an absence that constricts the heart. It is this perfection and how Ghadery delivers the story of Minoo’s unrequited and shame-filled love for her teenaged girlfriend; the gorgeous conversation with her son’s father; the moments with the mother in the end, an empathetic conversation with a neighbour – all of it will fill readers with empathy and love. Minoo needed her Ou (Ecology Paul) – he saved her – and I’m so happy I met them both.

Reading STAN ON GUARD I felt a twinge of excitement that in creating Ishtanu, an immortal “born in the Hittie Empire in the fifth year of the reign of King Muwattali the Second…about 1200 B.C. by current reckoning,” K.R. Wilson has opened a pandora’s box of juicy historical potential.

(Crossposted with Junction Reads’ Reviews. K.R. Wilson is coming to JR at TYPE Books Junction, April 12, 2026)

The second in the Stan books, STAN ON GUARD has the richness of detail with the perfect dose of exposition that fills in any blanks a reader may have – but I don’t think you’ll feel like you’re missing anything. While I urge anyone who hasn’t read CALL ME STAN to do so, once you’ve arrived in modern-day Toronto, where Tróán (another immortal) stalks Ishtanu, the man who killed her son 3000 years earlier – and whom she thought she’d murdered – and then once you’ve followed Tróán back to Ancient Greece, The Khanate, Lithuania and then Paris at the start of the last century, you will feel as though you belong to Tróán (she does have a way of pulling people into her circle). And then as you go back in time with Stan, you’ll be grateful for all you learn about Nietzche and the Great War, and you’ll be as surprised as I was at the lengths Stan takes to not return to the battlefields, as conscription is still in full swing.

With what must be Wilson’s characteristic intelligent historical humour, he’s given us a sequel to CALL ME STAN that is somehow funnier – how is that possible? When we get the asides describing the first book as Stan’s big mistake – that in allowing K.R. Wilson to write his story from a police interview, Tróán learns all she needs to find him and kill him once and for all, it just feels as though there can’t be any other way to perfectly blend these two sagas. Capturing unique moments in history that make the reader feel as though they’re walking the streets of Paris or trudging along the unpaved roads of ancient times, Wilson has given us (once again) an epic historical novel that is a thoroughly enjoyable read.

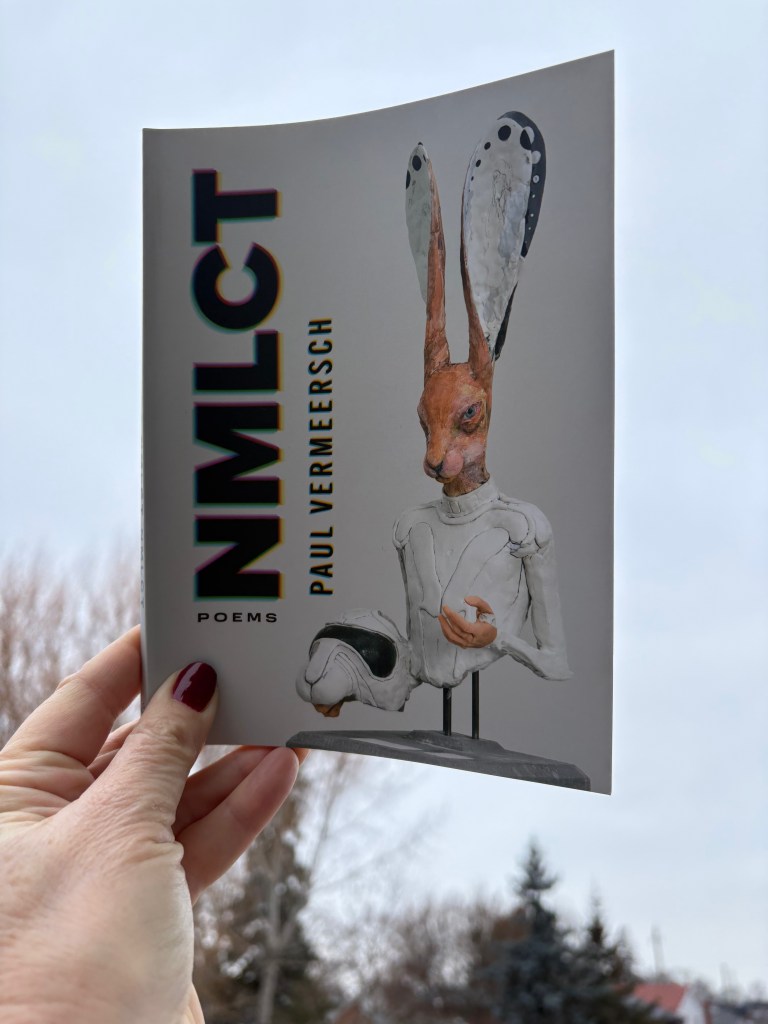

After reading Paul Vermeersch’s poetry collection NMLCT I closed my eyes. An image kept repeating itself. I am driving on an empty highway toward an abandoned city and on a billboard above the highway flashes an important message that I miss because I’m driving too fast. When I turn the car around to read the message again, the sign is gone and what I was supposed to do in this abandoned city, what I needed to know to fix the world, I no longer know. So, I read the book again.

The opening section MCHNCT (Machine City) is both apocalyptic in its imagined white space of buildings protruding from the ground; of wolves wandering aimlessly, but also preying and then dying, starving; of artificial intelligence; of oceans we’ve forgotten; of animals that appear as a matter of remembering, and of “eye contact, no longer analog.” I left MCHNCT feeling that I could have done more while I was there, instead, I saw and felt, outside looking in, just as people witness the devastating effects of capitalism and artificial intelligence, but do nothing, speak nothing.

In the NMLCT (Animal City) section, the wolves like winter, appear and disappear and while we know they’re there, they will return, they don’t feel real. We can only imagine, but the “knowledge of imaginary things is not itself imaginary.” In this section of the collection, I am more central, the reader, the body, the animals, I am a part of this “heavy, ancient” green, forest. But I am also living in a midway found by future generations, an indecipherable binary code of some strange existence. Who are we?

Vermeersch interrogates the artifice of life, of our very existence, how life (existence) is both a concrete thing that is right in front of us, all around, under us, and yet is also entirely a made-up thing. We are both animal and machine, but also, kind of neither, kind of in-between, in that mirrored box, a reflection of ourselves in the forest. I enjoyed wandering through this poetry collection because it reminded me to slow down and think about what is real, and therefore what I need to save myself from the world, and what the world needs to save it from itself.

STARRY STARRY NIGHT by Shani Mootoo, from Book*hug Press.

What does a reader want from a novel that you know is connected in many ways to the author’s personal history? A story written in the voice of a child who is physically rooted to a particular time and place, told with a unique presence of thought, as though the narrator were waking up each day and recalling the moments just as they happen. Moments we know are the emotional breath of the author’s childhood. STARRY STARRY NIGHT is more than I wanted it to be.

Spanning a few years in Trinidad, from primary school to convent school, from home to house, from neighbourhood to hillside mansion, Anju, a fictional narrator, tells us about her Ma and Pa, about how they raised her while her Mummy and Daddy went to school in Ireland. Anju expresses in the best way she can, the separation of her heart and body when her parents return and remove her from the only home she’s known. She describes the separation of mind and body as she experiences sexual abuse. She shares how desperately she wants to be a good girl, a good sister, a good daughter, even as she’s learning she “mustn’t bother to tell people your problems and mustn’t show your feelings to anyone.” Anjula is a talented young artist who sees her place, “Trinidad (and Tobago), West Indies, Caribbean, World, The Milky Way” reflected in the stars she wishes upon with her Pa, and she wonders, just as we all do, what is the meaning of all this living?

With the exact emotional voice of a young girl, one who doesn’t quite know who she is, but is seriously intent on knowing who she is, Mootoo delivers an introspective novel about learning how to grow up in a world that has separate rules for girls and boys. A novel of remembering, of the times in our lives we carry around like a precious and hefty rock in our back pocket. A novel about learning to be—for ourselves—who we want to be.

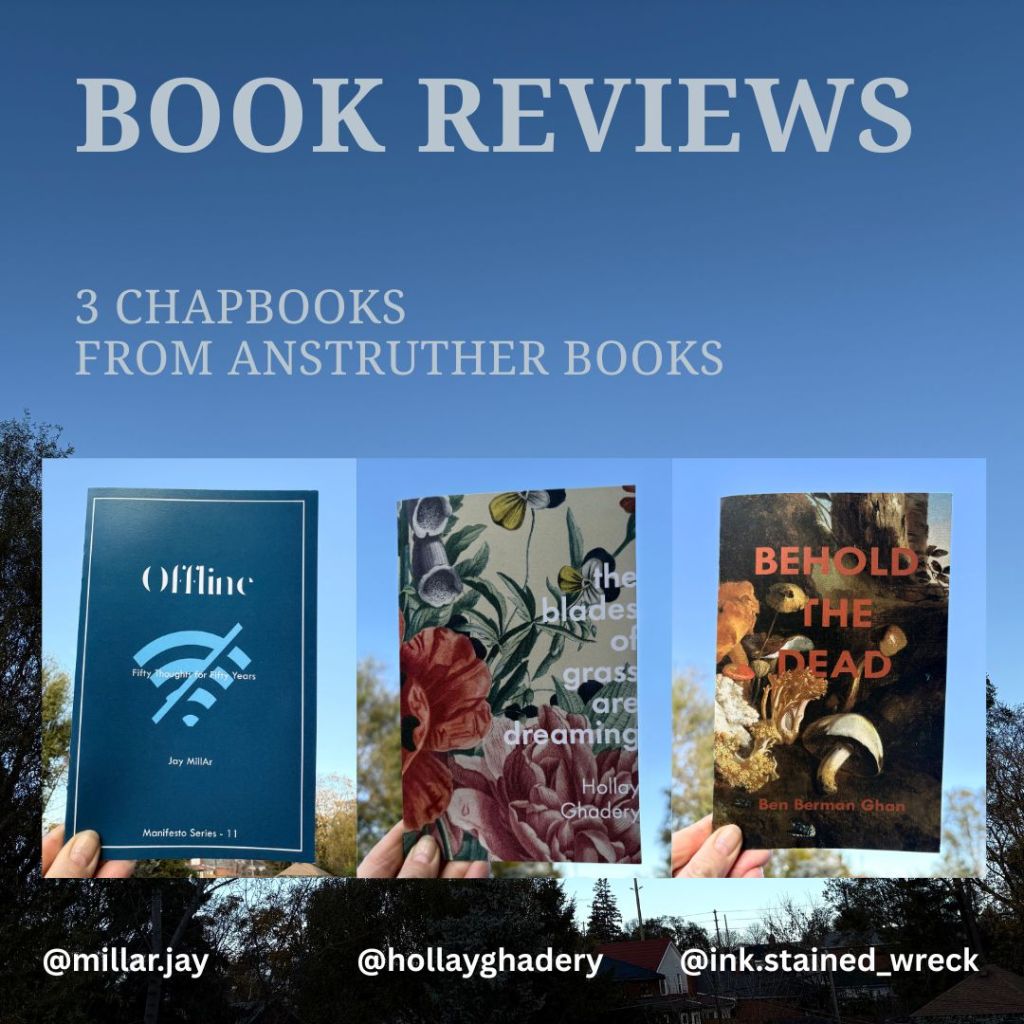

Three chapbooks from Anstruther Books. Jim Johnstone knows a great poem when he sees it! Check out their website for more titles, but you can read my very non-literary reviews of three titles. Jay MillAr’s Offline, Hollay Ghadery’s the blades of grass are dreaming, and Benjamin Berman Ghan’s BEHOLD THE DEAD.

There is a lot of Hollay Ghadery’s writing that makes me feel seen like no other collection of words can, but the opening poem, “Tuesday night love poem”, is an introvert’s hymn, a soothing cradling hug. Each piece in “the blades of grass are dreaming” are moments in time that remind me we’re all just stitched together, us humans, to our kids, to our parents, to the ones who die and remind us “the way you don’t know silence until someone disrupts it,” to the people we wait for and the ones who’ve been here all along. Ghadery exposes that fragile tethering like no other writer.

Jay MillAr. “Thinking is a practice that requires patience while mastering fear.” A collection of existence, of the why and how, of what it will feels like if it ends. A collection of thoughts saved from a non-communal social media platform. A critique of the internet as a postmodern framework “equivalent of God.” A collection of random thoughts that MillAr sometimes forgets to record (does that mean he’s “thoughtless?”) to mark his fifty years on the planet. A book about community and the heartbreaking fear that art and the creation of it might be a waste of time. God, I hope not! “Offline” is not an optimistic book, but it can be, if you turn it sideways, upside down, right side up and place yourself between the lines.

“Rotting and rotted subservient collaborative hunger eating all things.” A book of being, of moving toward un-being, “Eaten by what lives/what’s left/what thrives,” and of the rivers from which we demand more than they have. “Behold the Dead” a meditation on the ways we abandon ourselves to living, even when it is more obvious every day that we’re rotting from the inside, rushing towards death like none of this living means anything, that it ever meant anything. A fleshy sensual gift of poems, you think you know the human body in all the ways, until you read Benjamin Berman Ghan who exposes all the scars, bones, stretchmarks and cells in ways you’d never imagined.

When the beauty of the entire world exists inside the writing we share, the books we read, and that to write, and to read, we can feel “there’s hope despite all the bad shit in the world that you see every day.”

BIRD SUIT by @sydneyhegele is a unique and fantastically accurate story about broken people trying to exist as whole humans. A mythological tale of abandonment, sex, faith, death and love, this gorgeous novel asks big questions.

How do broken men hold so much power? Why does God allow bad things to happen to good people? What is love? Hegele offers a beautiful answer when they write, “who we’ve loved is…a history of who we are.” This moment drives home how deeply interconnected the people of Port Peter are, all carrying around the trauma of past generations—how deeply interconnected we all are.

The story is steeped in myth with birds who take abandoned babies and sirens who seduce men and birth their own bird-babies, a lighthouse, a beach preacher who performs exorcisms, a stage play called Bird Suit, and then there’s time. The novel moves back and forth between 1971 and 2019, like the memories we carry, the ones we try to forget, or pluck from our skin, that pierce our stories like a scream, including the memories we hold in our DNA. It centres Georgia, her mother Elsie, Felicity, her husband Arlo, their son Isaiah, his grandfather James. While we follow Georgia and feel the weight of her abandonment as a baby, and the awful abuse she experiences, it is Isaiah who writes poetry in the margins of books so his abusive father can’t read his words, it is Isaiah who tries to love, and it is he who feels like the spiritual heart of the novel.

One of the most satisfying endings I’ve read in a long time, I read it three times just to feel that character’s release again and again.

A book that remembers as best it can a childhood that exists in the shadows of grief, alcoholism, divorce, mental illness, heartbreak, and the unimaginable loss of a mother who can’t be grieved. Written with incredible skill, you can feel the pen gliding across every page in a whirl of emotion. WORLDLY GIRLS contains stand-alone essays that feel like fragments of a whole, a puzzle you only to realize is incomplete when you discover the missing pieces, what has been dropped, lost, or perhaps never packed into the box.

A model of how to collect one’s thoughts and relay them with honesty and a depth of emotion, it felt as though I were standing beside Jong as she ‘traced her past by visiting the places that had scared her as a child.’

Worldly is a word used by Jehovah’s Witnesses to describe, “a non-worshiper, unbeliever, outsider, someone who is “bad association” that can lead a Christian astray from Jehovah.” While Jong explores a life without the Witnesses, the religion floats around her too, and I felt the grief at losing religion as significantly as the death of Jong’s mother. As humans, we are desperate to belong, our connection to others is essential to our survival in so many ways, and when that connection is intrinsically tied to church, its loss can hollow us out in incomprehensible ways. I still dream of clinging to the pew, hanging on every word the Monsignor spit out of his mouth on Sunday mornings, belonging to something larger than myself, that today, as an atheist reading Tamara Jong’s memoir, I want to return to that hard wooden pew and feel whole again.

Reading Jong’s memoir reminds me that we are all wandering around, seeking and searching as Jong’s therapist says, holding on to childhoods that cannot be traced with words, that cannot be screamed into a pillow (Jong’s thoughts), childhoods that can only be revealed in slow details, in a deliberate and methodical unravelling of the moments that define us, the losses we carry with us forever. Jong made a record, and while she writes it is as much for herself as it is for others, reading Worldly Girls was something I really needed right now, and I’m grateful.

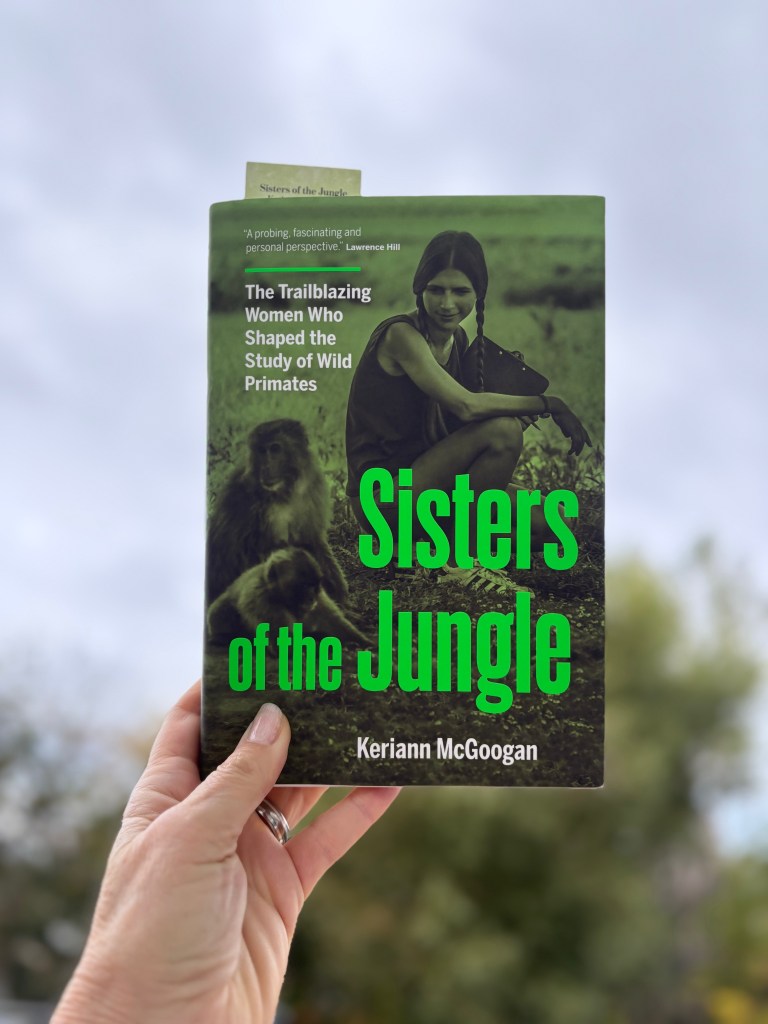

The “burning question” Keriann McGoogan explores in SISTERS OF THE JUNGLE is why are there so many women in primatology? My gut answer—as a woman with zero math or science skills—was that it seems like the safest field for women. With primatology trailblazers—the focus of McGoogan’s book—showing up on covers of National Geographic, in talk shows, bookshelves and Hollywood movies, appears more attractive to an 18-year-old than, let’s say, engineering.

McGoogan introduces chapters on Linda Fedigan, Dian Fossey, Jane Goodall, Birutè Galdikas, Jeanne Altmann, Sarah Hrdy, and Alison Jolly and a chapter for Louis Leaky (a very complicated male figure in primatology) with her own personal impressions of each subject, which invites the reader to consider what each of them might represent to young would-be scientists.

With Jane Goodall’s recent death, her chapter is probably the most moving because she set out a time when everyone expected less from her, and before she started her education she’d already done so much. She was just in Toronto in September. Her final message: “We have an opportunity ahead of us…if we get together with a passion for change…then we can make the change.” One of the most important themes in McGoogan’s book addresses conservation and the impact of climate change and environmental damage on primates.

Each subject is a real character (especially Leaky!) and they are brought to life with McGoogan’s great care and respect. SISTERS OF THE JUNGLE contains the fascinating, interconnected biographies of eight of the most influential personalities in primatology—nine if you consider McGoogan herself, which you should: she’s spent months collecting data on the lemurs (Coquerel’s sifakas to be precise) in Madagascar. If you haven’t seen the movie about Dian Fossey, her chapter will tell you exactly why Hollywood came knocking.

Why so many women? The answer to the burning question is more complicated than my own ideas, and McGoogan does a brilliant job of balancing the complexities of science and primatology as a particular field of study, with her own experiences and those of the most influential. As McGoogan says in her epilogue, it is astounding when you think what many of these women did at a time when they were expected to stay home. The question is not why then, but WHAT have they done? A great read that will trigger more conversation about this essential field of study.

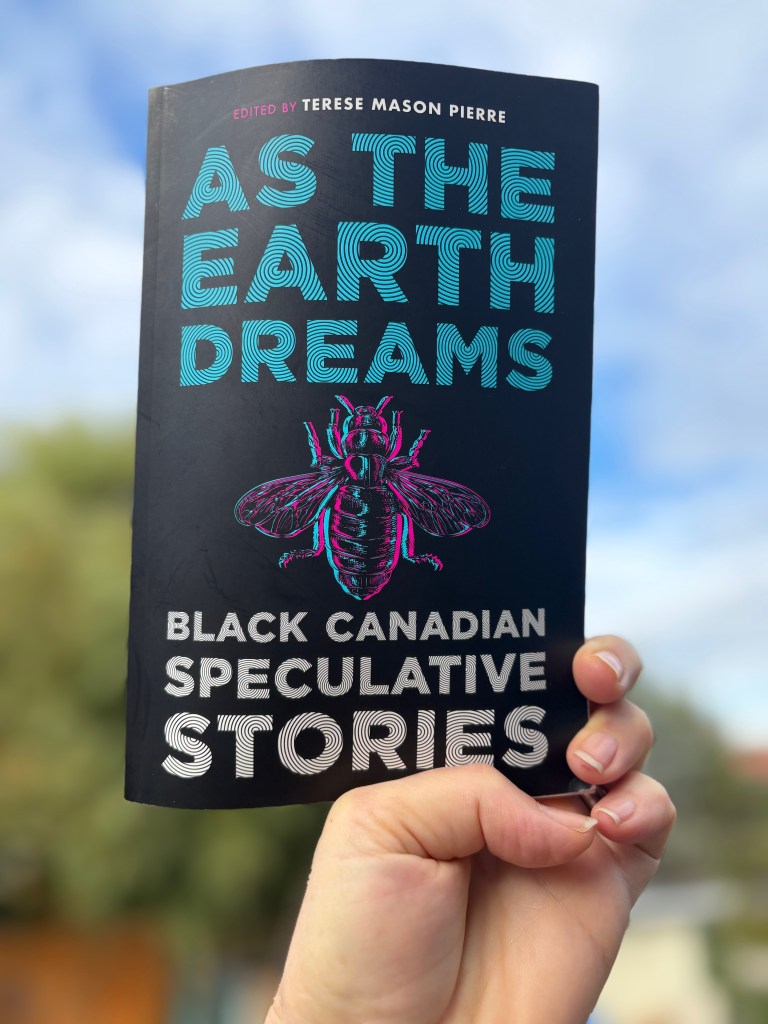

I love a great short story collection!!! There is no better anthology out right now than AS THE EARTH DREAMS, a collection of Black Canadian Speculative Stories, edited by Terese Mason Pierre. It should be on everyone’s must-read list.

In one story, the title narrator, Ravenous, Called Iffy, is a massage therapist whose mother keeps dying and whose kept a secret family, one the narrator fears she might love more than her.

In another, a woman who works as an appraiser at a Parkdale antiques shop, summons a spirit to give her the value of a ring, only the spirit tells her more about the ring and herself than she expected.

And another, a woman exists in a time where memories are harvested in order that black women’s children can be claimed and sold to the highest bidder.

In Hallelujah Here and Elsewhere, a woman experiences the traumatic separation of mind and a body that exists in the trauma childhood sexual abuse.

The stories in this essential collection share truths toward a common theme—that women’s bodies, black women’s bodies, are not their own, that they can be freely manipulated, used, lost, transformed, where “No one will hear, and no one will see what I am except me.” Days in these stories repeat themselves because these days exist in a world where time passes but nothing changes. There are childhoods drenched in darkness, with “rude shadows” looming above, an inescapable place where “the rich white folk can’t seem to birth babies on their own anymore.”

There are slips in time and memory where characters trip into worlds where they might find peace, an escape from the suffering that surrounds them like a malevolent stalker. There is also hope because love is a memory that cannot be erased. Friendship and family are places we can fly to and be safe. Speculative fiction holds the truth that often cannot be expressed in predictable plot points and tropes, and this collection expresses truth in so many dreamy, futuristic, magical, and imaginative ways.

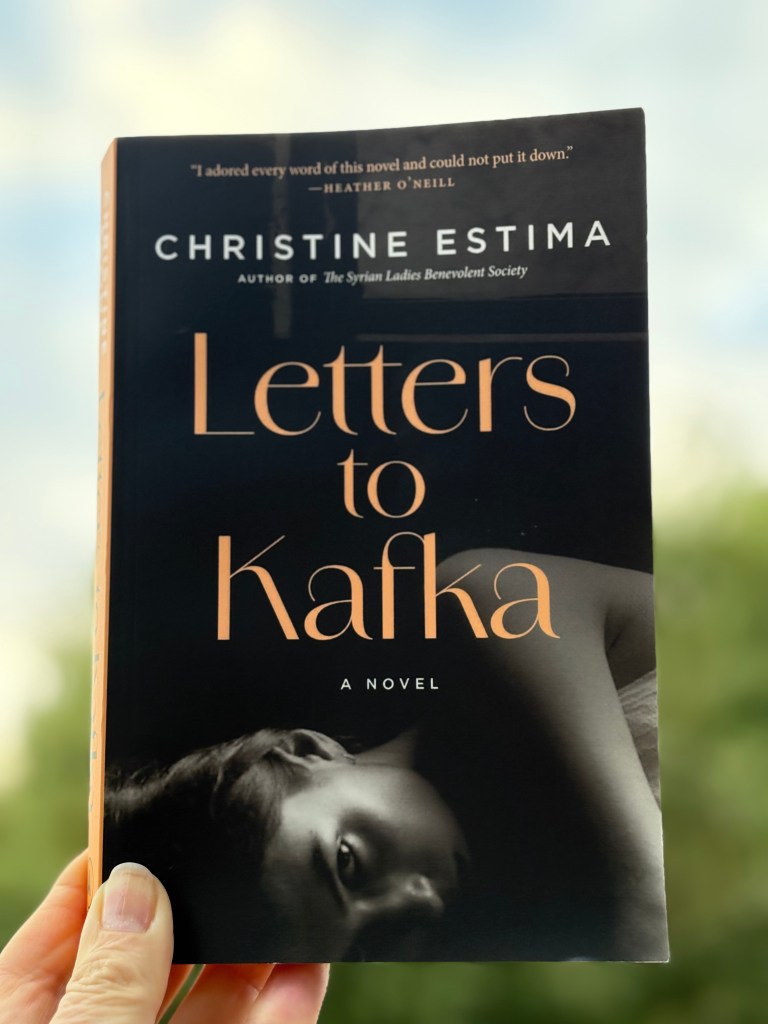

“Your letters were the most beautiful thing that ever happened to me in my life.” Franz Kafka to Milena Jesenská.

LETTERS TO KAFKA by Christine Estima is an intimate and emotional consideration of the life of a woman who wanted to be more than a wife, more than a beautiful object to be held, more than the recipient of Franz Kafka’s letters, which were published as Letters to Milena in 1952, almost 30 years after his death.

The novel opens in Prague in 1939 where Milena is being held in Pankrác Prison. While she sings through beatings in her “sessions” with the Obergruppenführer, we know her strength immediately. “You should be pitied, not feared” she says to him.

As we shift to first-person narrated sections, from 1918 to 1925, we see and understand Milena as closely as if we were standing in the same room. “I work so hard, and my man-about-town husband gives me no money. My misery is like luggage: every day I carry something heavier than the last.” Estima paints Milena in all her emotional layers—in fragments of time, in letters, telegrams, interactions, conversations, and walks through town—as an artist might paint his beloved muse.

The story unfolds like a housekeeper’s gossip—the kind that leaves you hanging on every juicy word—. Estima’s prose is vivid, sensual, breathing new life into the age-old story of a love that can never be anything but letters full of unrequited longing. Historical details feel like reader-candy to me with Freud sipping coffee and Klimt and the other artists and writers of the time flitting about. Time travel anyone?

There are very funny moments. When Milena fears her husband might move them to Canada! “Canada?! Where they strap blades to their feet and call it an Olympic sport? It’s barely even a country.” Or “I come from the Church of the United Sisterhood of I Don’t Give a Damn What You Think.“ Or “Your father would rather shit in his hands and clap before speaking to a pious Jew like me.“ There is brilliance on every page.

“There is an unstable burn that comes with being a woman among the fallout of men.”

Now, we have Milena’s story—finally. And it’s beautiful.

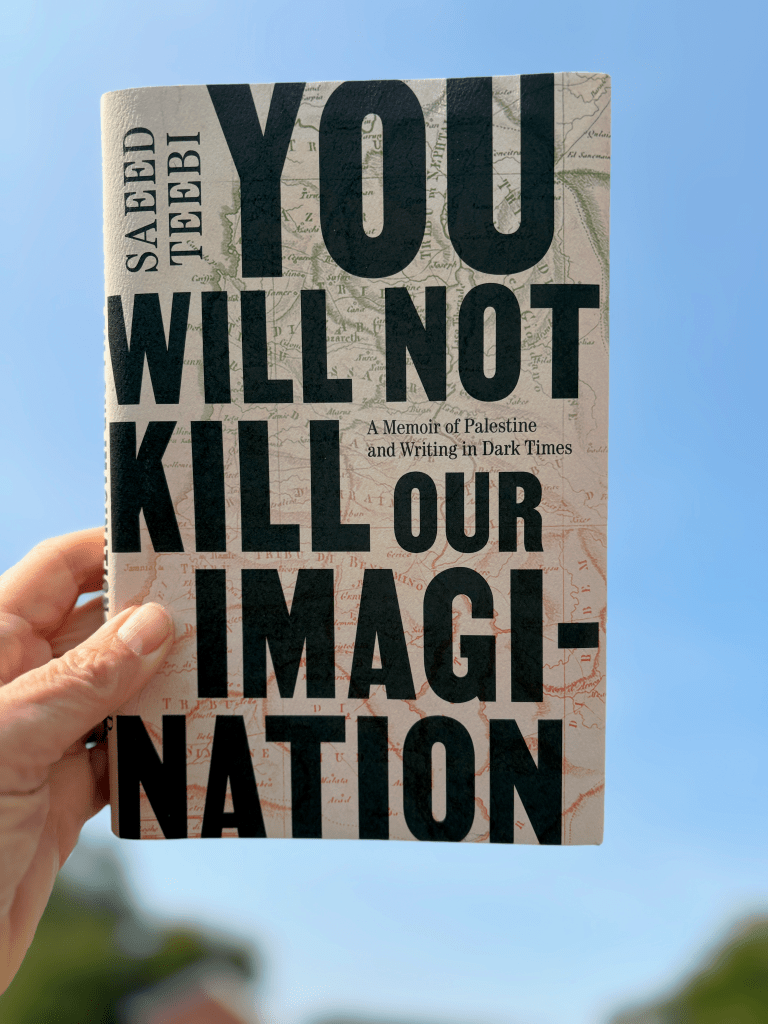

I wrote and deleted several lines to open my review of Saeed Teebi’s YOU WILL NOT KILL OUR IMAGINATION (Pub. 30/09/2025). But how can one sentence ever introduce the magnificence of this memoir? This book is for everyone—and its splendour is its mere existence as Teebi writes about loosening “the chains that once made anything like it possible.”

I am grateful to have read this book.

Here’s a list of attempts at opening lines:

1) This book will be a reference in a future essay about what it means to live in an era where an accepted historical truth was once forbidden. 2) This book is a reminder to all that while the silence and conformity of some might elicit empathy, “the gentleness doesn’t mean they haven’t failed, because they have.” 3) This book is a call to artists to “take on the challenge of writing a story that has not been written, that is forbidden to be written, a story that occurs in a history that has not been accepted.” 4) This book requires a notebook and a pen, for I believe every reader will have the pages of notations and quotes I am now reciting to memory.

In one essay, Platform and Safety, Teebi explores the role of the artist and the reasons regimes target artists and cultural institutions first. “…the artist is almost by definition a humanist. This means they have the potential to slash past the political and instead prioritise human values. Artists are uniquely positioned to take on the enormity of entrenched power relationships, and via their work foment further action.” An essential chapter for the writers of the world grappling with words, because there is no easy answer, especially for those whose jobs may be at risk, but it asks, where does your humanity live? I read the final chapter half a dozen times. Imagination. A manifesto as much as it is an elegy to past generations, the author’s father, who would no doubt feel the danger of writing such an honest book.

This book holds the heart of a people that will not be erased. It is a statue in the literary town square we’re erecting where future generations will safely sit and write their own stories, where they’ll find themselves and their ancestors, where they’ll be comforted by the truth.

In my dream of a life, where I have read all the beautiful short stories written by all the writers of the world, WHAT A FISH LOOKS LIKE by Syr Hayati Beker sits on a shelf staring back at me with the pupil-less eyes of a Mer, pleading with me to imagine a different world than the one we’re swimming toward now. Described a novella in fairy tales, each piece stands alone as its own poetically-voiced story of its big picture world.

This book collects “retellings of retellings…with a sense of wonder beyond our world,” fairy tales reimagined, a magical escape from expectations and my own trope-filled imagination (although I also do love a trope-filled story where I can shapeshift). It reminds us that “there might even still be time” to reconsider the carelessness and disregard for the oceans and the earth. You can always trust Stelliform Press to publish a book of tales that are as cautionary as they are magical, as heartbreaking as they are emotionally rich. These stories are about what we lose and who we lose (both by leaving and being left behind), when the oceans die. This book contains the stories that exist in the spaces between hope and loss, between love and abandonment, between what we want and what we allow to happen.

P.S. For every short story writer reading, grab a copy of this book! If you fear taking risks with your writing and escaping into your radiant mind—this is the collection to read. With letters, notes in a bar (an ex-bar), writings on a bathroom wall, full colour illustrations (descriptively written), invitations, community postings, Beker gives complexity and magic while swimming in the depths of their imagination. Brilliance lives here!

A Mouth Full of Salt, by Reem Gaafar: As we’re witnessing the conflict in Sudan – a civil war that began in April 2023 between the military and the RSF – that has now become the world’s worst humanitarian crisis, with more than 150,000 deaths and 12 million people displaced, it has never been more important to hear stories from Sudanese writers.

A MOUTH FULL OF SALT is the debut novel from Reem Gaafar, a writer, physician and filmmaker whose feminist perspective on Sudan and the African diaspora contributes to important conversations about gender and racial hierarchies, racism, tribalism, and the history of Sudan. Told between 1948 and 1989, the novel explores themes not exclusively Sudanese. Women everywhere are compelled to consider a complex network of expectations that often include familial, cultural, societal and the dreaded (as considered by Fatima, one of Gaafar’s female characters) how will my decisions affect my children, my grandchildren?

Gaafar has written a gripping mystery. How and why did the boy drown? What is killing all the animals? Who set the fires? Who is the woman in the mountains? How did Sawsan (a young bride) die? Gaafar has written a novel filled with heartbreak and pain. Nyamakeem, a southerner, falls in love with Hassan, a northerner who chooses wealth over his wife and young son, and we watch as she is swallowed up by a destiny that she worries she should have seen coming. It is a feminist critique of a society that values the birth of a baby boy over the life of his labouring mother. The scene where Sulafa assists her husband’s wife Sara give birth is truly heart wrenching, and one of the most harrowing moments I’ve read in a long time.

But more than all this, Gaafar has given us an emotionally rich narrative, written from an omniscient perspective that is also deeply reflective of each characters’ thoughts and experiences, that somehow left me feeling hopeful. Fatima and Sadig (cousins betrothed at birth) are an emblem of that hope, a sign that change is possible. Perhaps Fatima will not be trapped by the hierarchal rules. But like every great novel, this is only a story. We need more people to listen, more to read.

There is much to admire about K.J. Aiello’s book, THE MONSTER AND THE MIRROR. An exploration of mental illness, society’s perceptions with all its biases and tropes (so exploited and abused in film and television—why must mentally ill people always be the villain??), and a deeply personal journey through the liminality of mental illness when one lives between what is actual, and what is fantastically AND concretely real in the dark corners of our minds.

This book also offers compelling critical analyses of THE HAUNTING OF HILL HOUSE, THE LORD OF THE RINGS TRILOGY, Marvel superheroes, Dungeons and Dragons, video games, and THE LIGHT BETWEEN WORLDS exploring mental illness as metaphor. From a writerly perspective, this was super interesting. I also love a book with a reference page, especially when it offers more incredible work to read.

Aiello frames the non-fiction analyses with deeply personal stories from her life, which is where I felt less alone—and anyone else who grew up lonely, poor and scared of oneself might take solace. I’m not the only one who found the necessary safety, silence and magic inside books. I’m not the only one who was fed a head cheese sandwich (although it doesn’t sound like Aiello was forced to eat it like we were as kids).

But more than a book where the reader might share in the comfort of Aiello’s personal space, it should be seen as a tool for parents, educators, friends and healthcare workers to listen more keenly to the stories being told by those living with mental illness. There isn’t a prescriptive, objective reality—for any of us. Perception is as fluid as the wind, and experience changes with every breath we take, and with every word we read, and write. What I loved about this book more than anything, is it left me asking questions (and wanting to watch the TV adaptation of Shirley Jackson’s novel). The only way to find the answers is to keep reading about how others experience the world.

A bit more than a book review. As the mom of a kid with a facial difference, reading IT MUST BE BEAUTIFUL TO BE FINISHED by Kate Gies, I felt like I got to return to one of the thousand waiting rooms in our life to give that kid a hug.

I started reading this gorgeous book half a dozen times. I didn’t stop because of discomfort, but because I needed to sit with my thoughts, holding Kate’s words to my chest and feeling some things.

“It’s so hard as a parent — you’re making decisions that can affect your child’s whole life. You want to make the right decisions, but it isn’t always clear what those are.” Susan Gies, Kate’s mom, p. 271. I am Susan.

While some might see IT MUST BE BEAUTIFUL TO BE FINISHED as an essential read for anyone who shares Kate’s experiences getting “fixed” (and it is!), I want everyone else to read it. The idea that different or “disfigured” bodies need fixing comes from a societal push to create a (medically aligned) physical model of normal to which everyone should aspire. My husband and I were referred to a dermatologist and to “get the ball rolling on the laser treatments” we saw a plastic surgeon before we saw an ophthalmologist or neurologist – and so the actual life-threatening, and vision-threatening diagnoses of his rare condition came around the same time he got his first “spots”. The narrative structure demands that we pay attention to ALL the moments, big or small, that had an impact on Kate’s life, and the message is communicated in gorgeous and deeply emotional prose. Why must differences be “fixed” or “normalized?” “When is the renovation of one’s body over? What is the model of perfection?” “What is the line between healing and harming a body?” Kate has generously shared memories of a childhood , the grief at losing The Kate I Was Supposed To Be, the acceptance of self, the love of self, despite society’s insistence that she’d be happier if she were “fixed,” and I truly believe this and other memoirs from adults with similar experiences, should be essential reading for all the self-described normal-appearing folks, and it should probably be an essential read to anyone going into paediatric plastic surgery.

This is a book I will hold close to my heart forever.

Amanda Leduc’s WILD LIFE is a novel that will be experienced differently by every reader. I think this is the novel’s most remarkable achievement; we’re traveling together, but we’re not walking the same path.

It opens in 1908, as young Josiah – the novel’s prophet, and leader of the cultist “religious” Ladder-Days – speaks to animals and suffers two tragic losses. As the novel moves forward to 2041, the two constants are Bar and Kendrith, two hyenas, who, despite the species’ tendencies have become soul mates. They are Josiah’s feral disciples until they realize they are nothing more than proof for his pilgrims, plot points on his own maniacal path. As the hyenas follow the wind they encounter a signing gorilla and her pregnant caretaker, a Customer Engagement Representative on a seafaring train; a grieving widow, a deaf woman escaping an abusive partner; and a one-armed cellist (who owns a cello that plays itself). The characters are all connected in some way – some descendants of Bar and Kendrith’s original human connection – and there is a perfectly placed academic paper that fills in blanks about the thriving Ladder-Days cult that surges in popularity as time goes by. This academic paper chapter is a stroke of brilliance, as is the allusion to the tree from which the cello was born.

What is “wild” about the hyenas is that they accept their tendencies. Even as they’re learning what it means to be human, they are more human, offering Leduc’s truth bombs like, “Grief…like the opposite of hope.” and “We–– lost something. And we became different in the world after that.” Bar and Kendrith are called to help others who are struggling to be different in the world, to understand that it is the grief, the loss, the pain, the differences, that makes us all more “wild,” more human. Leduc has a knack for delivering brilliant truths inside the mythological, and giving us the painfully real in the form of a fairy tale. WILD LIFE is all that and more. It is the saga unfolding all around us and if we open our hearts and minds, we will find ourselves here, our whole bodies, our whole selves – wholly perfect and wholly wild.

Do you want to write a review or interview an author? Do you have a unique book, or collection of stories (Canadian only) that you’d like me to review? Contact us today at junctionreads@gmail.com.

More of my reviews can be found on Goodreads (I know, I hate Am@zon too, but people still use it to find books, so check out my profile.)